Title: Girls’ Last Tour

Format: Anime Series

Director: Takaharu Ozaki

Written by: Tsukumizu

LIGHT SPOILERS AHEAD! I made sure not to give away anything important in this review, but I do hint at some minor events and happenings in case you would like to see this anime completely fresh. However, I don’t think I give away anything with words that will ruin the experience of seeing the events with your own eyes.

Introduction

People complain all the time about how nothing is original anymore in movies or television. Everything these days is a sequel or reboot of existing IP’s. Blah, blah, blah.

However, on rare occasions, when the right creative minds meet under the proper alignment of stars, unique stories can make it through the producer gauntlet into mainstream availability. If you are so lucky to be in the right store or talking to the right friend or looking at the right streaming menu, you may have one of these rare gems fall in your lap and make you rethink what is possible in art and life.

For me, Girls’ Last Tour was one of those rare finds. The anime came out in 2017 based on a manga by the same name which ran from 2014 to 2018. The story follows the journey of two young girls dressed in army fatigues, Chito and Yuuri, who are driving a small Russian tank through a crumbling vacant city in the aftermath of war and just doing their best to survive.

If that sounds depressing, I’m going to be honest: at times it is—especially when you see how cute these characters are. (For western audiences, think Peanuts characters living in the remnants of a nuclear fallout.) There is really no reason why anyone would look at this show’s description and say, “That’s what I want to watch tonight!” The only reason I turned it on was because someone in a YouTube video ranked it among their top anime to watch. And I am so glad I did.

What often makes these “rare gem” stories stand out is when they juxtapose genres not usually seen together to create new and unique experiences. Cowboy Bebop, for example, mashed up westerns, film noir, and science fiction with a wildly diverse soundtrack. Neon Genesis Evangelion mashed giant robots with Judeo-Christian iconography and teen psychological drama. Girls’ Last Tour follows suit by taking the “slice-of-life” genre and placing it in a post-war apocalypse nearly devoid of human life.

I will dig more into what slice-of-life means below, but for now all you need to understand is that the style the GLT characters are drawn in and the types of stories being told in these episodes represent a specific aesthetic in anime and manga. Typically, but not always, the slice-of-life anime are about teenagers in high school and often revolve around a trope described as CGDCT or “cute girls doing cute things.” (More on that later.)

ALERT: I am going to attempt to explain why I think this anime and the manga are particularly special, but I am also certain this story is not going to be for everyone. If the cute characters, slow pace, soft music, and deep philosophical concepts are not going to keep your interest, I am not going to try to convince you something is wrong with your taste. (Anime is weird. I get it.)

However, if you are looking for a story that is truly unique, moving, and will make you think about it for a long time after it ends, here are some reasons why I personally think Girls’ Last Tour is amazing:

Where 20th Century Literature Meets 21st Century Pop Anime

If you have seen or read Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, the tone of GLT will feel very familiar to you. Girl’s Last Tour is less theatre of the absurd than Godot, but both stories take place in a bleak setting without clear motivations driving the characters. In Waiting for Godot we watch two characters waiting for someone to arrive by the road, but we aren’t really sure who or why. In Girls Last Tour, we watch two characters who are moving toward something, but we aren’t really sure where or why.

People sometimes describe the play Waiting for Godot to be about the purposelessness of life, and Girls Last Tour may fall into a similar category when looked at from a perspective of facing hopelessness in a dying world. However, I tend to believe both stories are less meant to focus on those themes as an end, but rather to use them as devices to bring focus to other aspects of the characters’ lives and personalities.

GLT offers us brief glimpses of the girls escaping a city engulfed in fighting through Chito’s dreams, but throughout the show we are only given small pieces of information about their past and even less about their plans for the future. In place of a larger mission, the stories are driven by the girls’ simpler motivations of survival such as finding food, fuel, and shelter.

Because the clues about Chito and Yuuri’s past and future are so sparse, the show rather ingeniously forces our attention on their present moment at all times: what do they desire in that moment? How do they deal with their present obstacle? What are their feelings at present? And, perhaps most touching of all, where do they find joy?

Slice-of-life is often criticized by viewers who are used to scripts with more high stakes conflicts because these stories tend to feel slow paced by comparison. Characters are simply living their lives. Sometimes that may mean getting a job or winning a game or asking a girl on a date. These are conflicts for sure. Their ordinary nature makes them feel more low stake, however, and often one episode’s conflict has little relation to conflicts confronted in the next episode.

That is not to say the characters in GLT are not put in danger in any way. Quite the opposite, the huge structures surrounding them seem to be a constant threat of either falling on them or of the girls accidentally falling off. But therein lies the show’s characteristic contradiction: in a world we would normally expect to see two strong women hardened by survival in an unforgiving environment, we are instead watching two children figuring out what everyday items like a radio or map were used for in a by-gone world.

This particular style of slice-of-life story falls into a category known as “iyashikei” which translates to “healing type”. These anime are generally comforting anime to watch because the characters are drawn in a cute style, have charming interactions with each other, and even in the face of trouble, generally come out okay on the other side.

(Why it is often “cute girls doing cute things” in these stories rather than “cute boys doing cute things” I can only guess, but it may have something to do with the history of manga in Japan. Since the early days of manga, there were specific stories made for girls (Shouja) which focused more on cute art and for boys (Shonen) which focus more on action oriented art. I am sure there is a lot more to it than that, but that’s a question for someone with more knowledge of Japanese comics than me.)

As these simple characters keep moving forward despite the bleakness of their environment, we get to see them make sense of the world on their own terms. This understanding usually derives from a combination of the little information Chito has read in books and (illiterate) Yuuri’s emotional and biological responses to any given moment. Questions arise as they piece together what things were and why people made them:

What are drain pipes? Why do you write in a journal? How do you make airplanes fly? What is baking? Why do you take a photograph? What are graves for? What is beer?

While researching the slice-of-life genre, I came across an interesting video essay where the vlogger likens this genre to a concept born in early twentieth century literature called “defamiliarization.” The video maker references rather heavily a Russian Formalist named Viktor Shklovsky who describes the concept as such:

“It makes the familiar seem strange by describing it as if we were experiencing it for the first time.”

By placing characters in situations where they are forced to examine the ordinary and make sense of it in a new or unusual context, our perception of such things are taken out of our subconscious mind and placed into consciousness. The object of defamiliarization in art, as Shklovsky would describe it, is to slow our perception of things common to us in life long enough to examine and appreciate their beauty with fresh perspective.

For example, take an ordinary activity like slicing vegetables for a meal. If we do it every day, the action becomes so habitual and part of our daily routine that we may forget on some days that we even did the action at all. But when observing a character acting out those routines in animation (e.g. characters preparing meals in a Studio Ghibli film), the experience takes on a heightened vividness because all our senses are suddenly awakened to such a familiar activity. We can feel the knife cut through the tomato, the juices that leak out, the smell, the anticipation of taste, etc.

As with Chito and Yuuri enjoying the excitement of tasting chocolate or seeing automatic street lights come on at night, the real life beauty of simple things becomes noticeable only through the eyes of these characters experiencing them for the first time. As Shklovsky says:

“Art exists that one may recover the sensation of life. It exists to make one feel things. To make the stone stoney. The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known.”

Contemplating the End of Humanity Over Some Yummy Snacks

All of these aspects of the slice-of-life genre take on a particularly poignant meaning when you consider these two characters may be the last human characters to see any of it at all. It begs you to ponder deeper questions about what is the meaning of humanity if it eventually just ends?

Through it all, though, the show presents all of these darker concepts not through a lens of hope but rather through one of making peace with hopelessness. The point seems to be, from my perspective anyway, that if the end of humanity is coming anyway or the end of a human life at least, how do we cope? What do any of the trappings of human creativity mean when there are no humans left to observe them?

In the case of Chito and Yuuri, it may be simply innocence that allows them to continue in the face of their daunting obstacles. In moments when it seems Chito is getting to contemplative or Yuuri is getting too dark and destructive, the girls quickly end the downward spirals with a quick cartoonish bonk on the head, a sarcastic jab, or their favorite, a quiet moment savoring some yummy rations.

Even so, watching them live life in the moment, never being stupidly optimistic yet also never being stubbornly joyless feels very genuine and relatable. Like the way humans often behave in real life in general—apocalypse or no apocalypse. The inner world of human experience seems to boil down to that constant tension between wondering if this life is all just a futile effort and knowing deep down there is something here still worth enjoying.

The Manga Ending vs the Anime Ending

The GLT manga has a total of six volumes, and the show ends at the end of the fourth. After finishing the anime, I had to find the rest of the chapters online to see how the girls’ journey ends.

The ending of the anime has its own deeper meanings and ends on a lighter note than the manga. However, if you are able to read the last two volumes of the manga, the ending of the girls’ journey is much more somber and profound. It leaves you with the feeling that it couldn’t end any other way, and yet the journey was still so worthwhile.

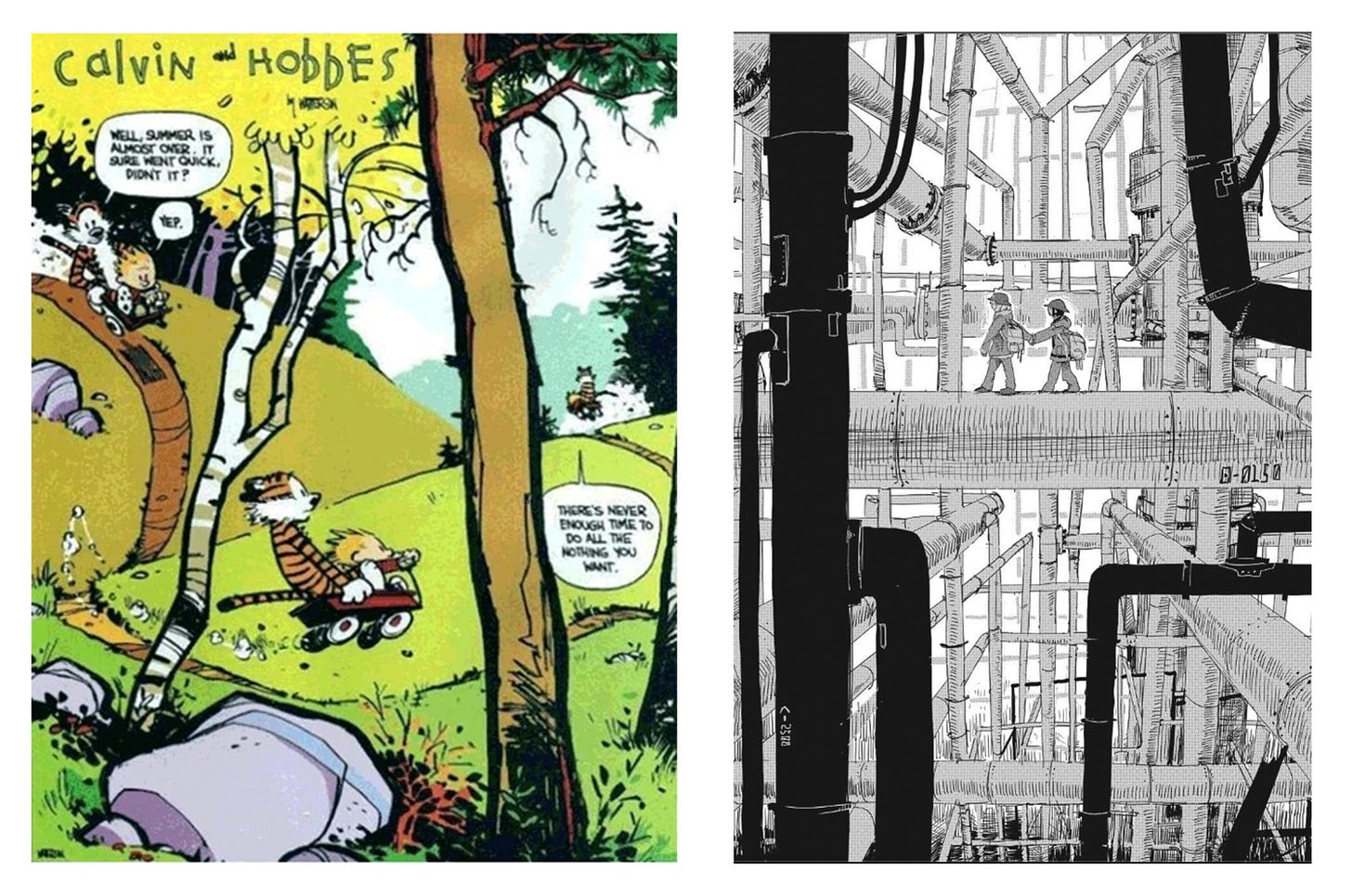

Though different in tone completely, the GLT manga is similar to Calvin and Hobbes in that it uses comic art to the peak of its faculties to philosophically examine human life. The characters are drawn in a very comic strip style with their large eyes and potato shaped heads, but when the author, Tsukumizu, sets them against the larger set pieces of the city as Bill Watterson does with placing Calvin and Hobbes against a backdrop of nature, we are invited to ponder our place in a much larger universe.

I think the animated characters, the voice acting, and the music bring so much more to the story the manga cannot. However, I also cannot imagine seeing the ending of the story told in animation, and it having quite the same personal impact on me as when I read it on paper. It is truly exquisite, and I recommend anyone who watches the anime to go find it.

What the Manga Can’t Do: Music & Voice Acting

Aside from the story, I cannot talk about this show without giving a nod to the performances of the Japanese actresses and the music in the show.

When I watched it on Amazon Prime, the English dub track was not available, but I think I prefer it that way. The performances of the two main voice actresses (Inori Minase and Yurika Kubo) add so much to these characters. There are also certain moments where I think the humor would be lost without the original Japanese words being said, which I won’t spoil here.

Behind the voices, the music of this anime is one of the most enchanting and remarkable scores I have heard in a long time. The mix of harps, pianos, and other strings with ethereal choirs perfectly compliments the story’s strange spirit of innocence floating on the surface of destruction. For me, it blended so seamlessly with the surreal landscapes that, at times, it seemed as if the music was emerging from my own subconscious rather than from the show itself.

In contrast to the score, the opening and closing credit songs are a sort of happy, Japanese electro-pop. (I hope my nephew will forgive me if I don’t know the proper name for the music style.) These songs are actually sung by the voice actresses in the show which ties the music to the characters in a unique way. In the background tracks, you hear sounds familiar in nostalgic video games, and the animation shows the girls dancing in their fatigues the way you might see typical teenagers dancing today on Tik-Tok.

These sequences seem completely at odds with the theme of the show where these characters know nothing about these games, dances, or even the lively spirit of the music. They live in a post-war apocalypse, after all. Yet as part of the overall experience of the show, seeing the girls in these perspectives allows an opportunity for us to see a glimpse of perhaps what they should have been in a more normal human world.

They are young girls, probably teenagers, who by all rights should be behaving like teenagers do at any given moment. In those quiet moments when they are enjoying the taste of a fish for the first time or staring up at the stars, you can imagine who they are in relation to our own world. And just the thought of that makes you love them and hurt for them all the more.

Conclusion

As morose as the themes about war and the end of humanity may sound, I found this anime to be oddly pleasant and beautiful to watch. Between watching the girls funny interactions, the pleasure on their faces whenever they eat just about anything, the lovely music, and their never ending will to keep moving forward, the show never quite seems to lose the “iyashikei” spirit to which it owes much of its inspiration.

For me, it was a great show to turn on at the end of the day to quiet down all the noise of the world before turning in for bed. Many of the themes about war feel eerily relevant to current world events, and it is one I still find popping up in my mind weeks after having read the ending of the manga.

So for anyone looking for something different, Girl's’ Last Tour is truly a story that is unlike anything else you will find in the east or west.

SIDE NOTE: I loved the music from this show so much that I had to import it from Japan so I could listen to it on my Itunes. Unfortunately, you can’t buy it in the US on ITunes, but you can find recordings of the music on YouTube if you like. I’m adding a good one to the bonus links below.

BONUS LINKS:

Philosophy of Slice of Life Video Essay

Opening Sequence and Song from GLT

Sterling Martin is a writer, artist, and designer living in Chicago, IL. His background includes drawing, writing, theatre, teaching, improv & sketch comedy, and whatever else he can get his hands on to be creative. You can find him on the internet at:

Instagram: @sterfest.art

Website: sterlingmartin.design

Tik-tok: That’s the one you make videos, right?

Linkedin: I’m pretty sure I have one of those

Facebook: Ugh, do I have to?